Liberté, 30 juin 1941

Légende :

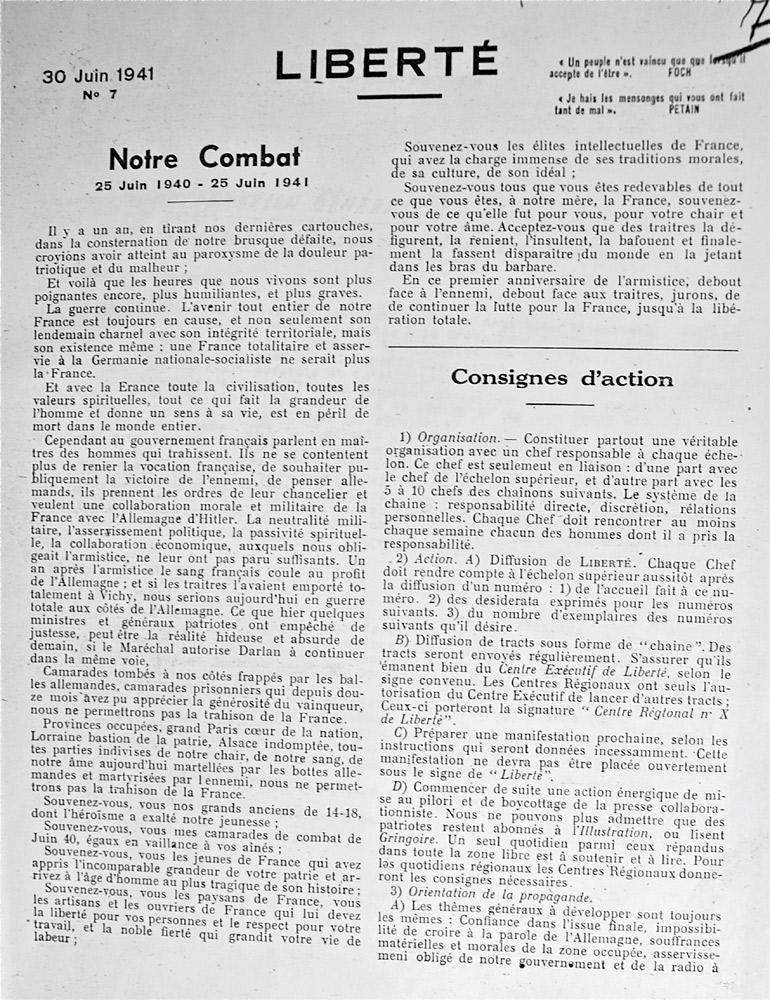

Une du journal Liberté n°7, 30 juin 1941

Front page of the newspaper “Liberté”, number 7 from June 30th1941

Genre : Image

Type : Presse clandestine

Producteur : Bibliothèque Nationale de France (BNF)

Source : © BNF - Gallica Droits réservés

Détails techniques :

Journal imprimé

Date document : 30 juin 1941

Lieu : France

Analyse média

Ce journal, dont les premiers numéros se réduisent à un tract, est basé à Marseille et a été fondé en 1940 par François de Menthon, Pierre-Henri Teitgen, Paul Coste-Fleuret, et Rémy Roure qui en assure la rédaction avec Roger Nathan Murat.

A la fin de 1941, Liberté fusionne avec le journal Vérités d’Henri Frenay et donne naissance à Combat. Liberté est organisé en deux colonnes réparties en deux articles de longueur inégale, mais qui se placent à des points de vue différents : le premier article – dans un style souvent oratoire – est une recension des vicissitudes que la France vient de connaître et de toutes les conséquences qui en résultent, tandis que le second article – qui prolonge, de façon concrète, l’appel à résister clôturant le précédent article – préconise une suite de consignes pour les actions à mener.

This paper, which originally started as a small pamphlet published out of Marseilles and founded in 1940 by François de Menthon, Pierre-Henri Teitgen, Paul Coste-Fleuret and Rémy Roure who wrote for the paper with Roger Nathan Murat. At the end of 1941, “Liberté” combined with Henri Frenay's paper “Vérités”, giving birth to the newspaper “Combat”. “Liberté” was organized around two articles, unequal in length and addressed different points of view: the first written in a more oratorical style review of different vicissitudes that France had just begun to experience and all the resulting consequences. The second article prolongs the previous article in a more concrete approach, the call to resist that closes the first article and advocates for readers to take action.

Alain Giacomi

Traduction : Sarah Buckowski

Contexte historique

Sur le journal (1)

Le 25 novembre 1940 est diffusé en zone Sud le journal Liberté. Fondé par les professeurs de droit François de Menthon et Pierre-Henri Teitgen, imprimé à Marseille, il recrute ses militants dans les milieux démocrates-chrétiens. Autour de son journal, un mouvement s'étend sur la région de Lyon et dans le Sud-Ouest. Hostile à la collaboration, Liberté soutient d'abord le maréchal Pétain et sa politique intérieure puis s'en détache lentement au cours de l'année 1941. A la fin de cette même année, Liberté fusionne avec Vérités pour former Combat.

Sur les événements de la période (2)

Ce numéro paraît un an après la signature de l’armistice avec l’Allemagne, à un moment où une résistance s’organise et veut prouver son existence au grand jour, mais aussi où la Collaboration se met en place avec, le 9 février 1941, la nomination de l’amiral de la flotte François Darlan comme vice-premier ministre et ministre des Affaires étrangères. La politique de collaboration qu’il développe dans les mois qui suivent se concrétise par la signature avec Otto Abetz des Protocoles de Paris, le 28 mai. Ceux-ci font une suite de concessions aux nazis qui obtiennent ainsi une base pour la Luftwaffe en Syrie, du matériel militaire, ou encore des bases navales à Bizerte et à Dakar.

Dans la zone sud, non-occupée, les jugements concernant le maréchal Pétain et le gouvernement de Vichy sont partagés et parfois ambigus. Si la collaboration est largement dénoncée par les mouvements de Résistance naissants, beaucoup croient en la personne du maréchal Pétain, dont ils pensent la politique modérée. C’est le cas dans ce numéro de Liberté où Pétain est opposé aux « véritables collaborateurs » comme Darlan.

En mars 1941, a lieu à Marseille la première manifestation de rue hostile aux occupants, en soutien à Pierre II de Yougoslavie pour son opposition aux sympathisants de l’Axe. Celle-ci prend la forme de dépôts de fleurs aux deux endroits commémorant l’assassinat du roi Alexandre 1er. Cette manifestation s’accompagne d’une effervescence dans les différents établissements scolaires de la ville. Par la suite, l’écoute de la radio de Londres et la pénurie du ravitaillement aidant, les inscriptions et les tracts gaullistes et anglophiles se multiplient.

The newspaper

This paper was distributed on November 25th 1940 in the Southern zone. “Liberté”, founded by law professors François de Menthon and Pierre-Henri Teitgen, printed in Marseilles, recruited militants often identified as democratic-Christians. A movement developed around the paper in the SouthWest and the Lyon region. Clearly against the collaboration, “Liberté” first supported Marshal Pétain and his domestic politics then moving away in the course of 1941. At the end of the year, “Liberté” joined forces with the fellow clandestine newspaper, “Verités” to form the newspaper, “Combat”.

On the Events during the Period

This edition was printed one year after the signing of the Armistice with Germany, during a time when the Résistance was beginning to organize and wanted to prove its existence publically, but as well as the time when the Collaboration was at a turning point with the appointment of Fleet Admiral François Darland to the position of vice Prime Minister and minister of Foreign Affairs on February 9th 1941. The politics of collaboration that he wished took shape in the following months with the signing of Protocols of Paris with Otto Abetz on May 28th. Through these protocols the Vichy Government allowed the Nazis to seize control of an airbase that they would use for the Luftwaffe, in Syria, as well as military equipment and naval bases in Bizerte and Dakar.

In the non-occupied southern zone the public opinion over the collaboration and the Vichy government was split and often ambiguous. Though the collaboration was largely denounced by the early Résistance movements many people believed in Pétain, whose politics they perceived as moderate. This was the case in the edition of “Liberté” where Pétain was opposed to “genuine collaborators”, such as Darlan.

In March 1941, a hostile protest against the Occupying forces took place in the streets of Marseilles, in support of Pierre II of Yugoslavia for his opposition to the Axis powers. Flowers were placed at two memorial sites commemorating the assassination of King Alexander 1st. This protest was accompanied by a bubbling up of different educational establishments throughout the city. Afterwards there was an increase in listeners to Radio London and subscribers to Gaullist and pro-British pamphlets multiplied.

Cécile Vast, "Liberté" in Dictionnaire historique de la Résistance, sous la direction de François Marcot, Robert Laffont, Bouquins, Paris, 2006 (1).

Alain Giacomi (2)

Traduction : Sarah Buckowski

Voir le bloc-notes

()

Voir le bloc-notes

()