Tract 14 juillet de Combat, 14 juillet de Victoire, Nice, 1943

Légende :

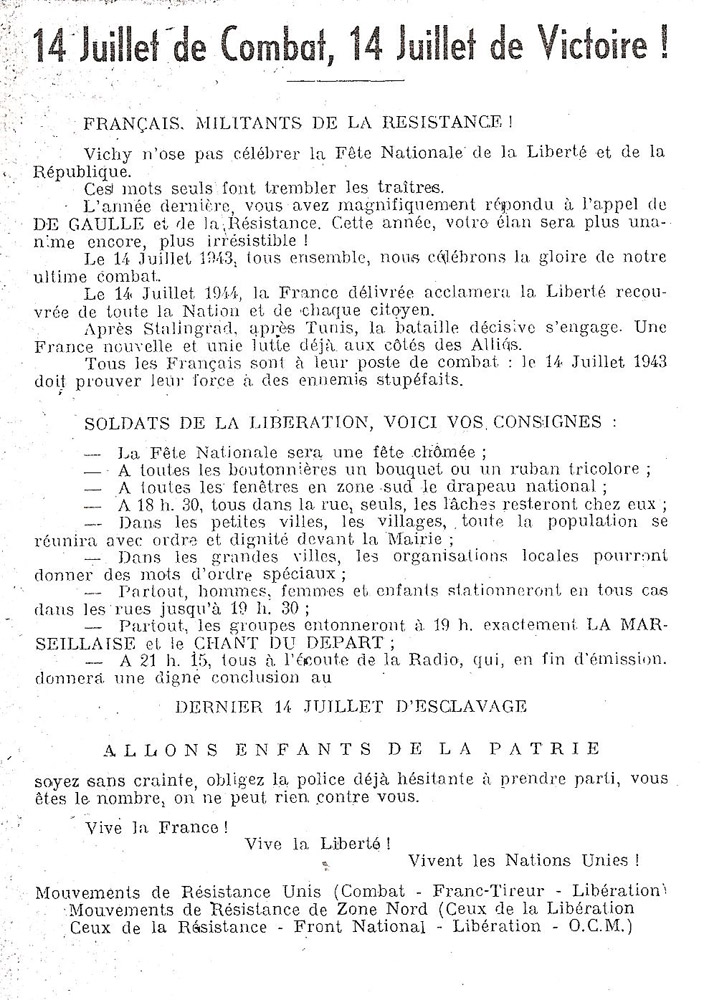

Tract intitulé "14 juillet de Combat, 14 juillet de Victoire" appelant à manifester le 14 juillet 1943 diffusé dans les Alpes-Maritimes

Leaflet entitled “14 juillet de Combat, 14 juillet de Victoire” (July 14th Fight, July 14th Victory) calling for protests the 14th of July 1943 in the department of Alpes-Maritimes

Genre : Image

Type : Tract

Source : © Archives départementales des Alpes-Maritimes Droits réservés

Date document : 14 juillet 1943

Lieu : France - Provence-Alpes-Côte-d'Azur - Alpes-Maritimes - Nice

Analyse média

Le tract signé par huit mouvements de Résistance de zone Nord et de zone Sud appelle à manifester, en 1943, pour le 14 juillet, « Fête nationale de la Liberté et de la République ». Il dénonce le refus de Vichy de toute commémoration républicaine et rappelle les importantes mobilisations du 14 juillet 1942. Il annonce que le 14 juillet 1944 sera celui d’une Libération dont les victoires en Afrique du Nord et à Stalingrad sont les prémices. « Victoire » et Combat » sont les maîtres mots pour les manifestations de 1943 qui doivent être une démonstration de force. L’ensemble de la population, « hommes, femmes et enfants » est appelé au « poste de combat ».

Certaines consignes sont à peu près les mêmes que celles de l’année précédente : on doit hisser le drapeau tricolore aux fenêtres et porter les trois couleurs. Les manifestations, prévues à 18 heures 30, comportent trois niveaux. Deux sont assez bien définis : partout, déambulation dans les rues, jusqu’à 19 heures 30, avec chant de La Marseillaise et du Chant du départ à 19 heures, et, dans les petites villes, rassemblement devant les mairies. En revanche, des instructions précises sont à venir pour les grandes villes.

Il existe des différences importantes avec les appels pour le 14 juillet 1942. La principale est que la mobilisation doit toucher l’ensemble du territoire, ainsi que l’indiquent les signatures des mouvements de zone Nord et de zone Sud. C’est ce qui explique peut-être, en partie, le flou à propos des grandes villes. Mais surtout, désormais, toutes les manifestations se font en territoire occupé (les troupes allemandes et italiennes ont investi la zone libre en novembre 1942). Même si la police hésite à prendre parti, des heurts avec les occupants sont à craindre dans les grandes agglomérations.

The leaflet, issued jointly by eight sub-groups of the Resistance movement of both zone Nord and zone Sud, calls for protests on France’s national holiday, July 14th, in 1943 “Fête nationale de la Liberté et de la République” (National Celebration of Liberty and the Republic). It denounces the Vichy government’s refusal to commemorate the country’s republican legacy and recalls the importance of the July 14th protests of 1942. The leaflet proclaims that the celebrations of the 14th of July 1944 will be ones of liberations, with the victories in North Africa and Stalingrad serving as prophetic examples of this inevitability. “Victory” and “Fight” are the key words for these protests of 1943, which must be a collective demonstration of force. The entire population “men, women, and children” are called upon to participate.

Several of the leaflet’s instructions are more or less the same as those provided the previous year, such as the instructions given to hang the tricolored flag in windows and to sport the national colors. The protests, predicted to begin at 6:30 p.m., comprised three stages. Two are well defined in the leaflet: 1) wander throughout the streets until 7:30 p.m. while singing the La Marseillaise and Le Chant du depart until 7:00 p.m. 2) in small towns, rally in front of the town halls. On the other hand, precise instructions for large towns and cities had yet to be released.

There were several important differences between these appeals and those disseminated for the protests of July 14th, 1942. The primary difference is that these protests needed to form a type of social mobilization that reached the entire the country, as indicated by the collection of signatures of sub-groups from both the zone Nord and the zone Sud. This perhaps partially explains the lack of clarity regarding instructions for large towns and cities. Most importantly, henceforth all of these protests were to occur on occupied territory, as German and Italian troupes invaded the free Zone ("zone libre") in November of 1942. And even if the police were to hesitate in taking sides, collisions with the occupants were still feared in large urban areas.

Jean-Louis Panicacci et Robert Mencherini

Traduction : Sawnie Smith

Contexte historique

Cet appel pour le 14 juillet 1943 intervient au moment où les armes commencent à être très favorables aux Alliés, ainsi que le mentionne le tract : sur le front Est, en février 1943, défaite allemande à Stalingrad, et, en Tunisie, en mai 1943, capitulation des forces de l’Axe qui ouvre la voie au débarquement en Sicile, le 10 juillet 1943.

Ce texte évoque une « France unie ». En juin 1943 a été créé, à Alger, le Comité français de Libération nationale (CFLN) sous la double présidence des généraux de Gaulle et Giraud. L’appel signale que la France « lutte aux côtés des Alliés » : les troupes françaises ont pris toute leur part des combats en Afrique du Nord. Elles vont continuer en Italie.

En France métropolitaine, un tournant a également été opéré. Les principales forces de Résistance, de zone Nord et de zone Sud, se sont unies, en mai 1943, sous la présidence de Jean Moulin, au sein du CNR. Celui-ci s’est placé sous l’autorité du général de Gaulle. Les huit mouvements signataires du tract sont membres du CNR.

Ces circonstances laissent espérer une libération proche, explicitement annoncée pour l’été 1944. Elles expliquent aussi, sans doute, que cet appel se place beaucoup plus sous le signe du « combat » que sous celui de la commémoration.

Dans les Alpes-Maritimes, où ce tract a été découvert par la police, les renseignements généraux notent que le matin du 14 juillet 1943, à Nice, le pavoisement des immeubles « a été insignifiant ». En revanche, dans la soirée, un millier de personnes se sont regroupées dans le centre-ville. Une centaine de personnes ont manifesté, avec un drapeau tricolore, en chantant La Marseillaise, avant d’être dispersées par les forces de police.

This appeal for protests on the 14th of July 1943 was published just as the trajectory of the war began to favor the Allied forces, and consequently why the leaflet mentions the German defeat in Stalingrad on the Eastern Front in February of 1943 and in Tunisia in May 1943, when the surrender of the Axis forces allowed for the landing of Allied troops on the shores of Sicily the 10th of July, 1943.

The text evokes the notion of a “France unie” (unified France). In June 1943, under the direction of Generals de Gaulle and Giraud, the Comité français de Libération nationale (CFLN) was created in Algiers. This decisive action broadcasted to the world that France “fights on the side of the Allies”. Consequently, French troops took part in the combat in North Africa and would continue their participation in Italy.

A turning point had also occurred in Metropolitan France. The main forces of the Resistance, those of zone Nord and zone Sud, were united in May 1943 under the direction of Jean Moulin and formed the Conseil National de la Résistance (CNR, National Council of the Resistance). Moulin was appointed the leader of this operation by General de Gaulle. All eight of the sub-groups that issued this leaflet would become members of the CNR.

These developments allowed room for hope of imminent liberation, explicitly announced in the summer of 1944. They also arguably explain why the political emphasis of this leaflet is that of “combat” versus commemoration.

In the department of Alpes-Maritime, where this leaflet was eventually discovered by the police, general sources state that in Nice, on the morning of July 14th, 1943, the level of solidarity and patriotic pageantry visible on the buildings “was insignificant” (recall the instructions given to hang the tricolored flag in all windows). However, by the evening, around a thousand people gathered in the city center. Around one hundred people protested, waiving a tricolored flag and singing La Marseillaise before being forcibly dispersed by the police.

Robert Mencherini, "Autour des manifestations du 1er-Mai et du 14-Juillet-1942 à Marseille et dans les Bouches-du-Rhône", in Résistance et Occupation, 1940-1944. Midi Rouge, ombres et lumières. Histoire politique et sociale de Marseille et des Bouches-du-Rhône, 1930-1950, tome 3, Paris, Editions Syllepse, 2011.

Pour les manifestations dans les Alpes-Maritimes : d’après Jean-Louis Panicacci (dir.) La Résistance azuréenne, Nice, Éditions Serre, 1994, p. 34 et rapport des renseignements généraux, p. 216.

Traduction : Sawnie Smith

Voir le bloc-notes

()

Voir le bloc-notes

()